In 1446, William, the last Sinclair Prince of Orkney, began building a church to be called the Collegiate Chapel of St Matthew on the lands given to him in Scotland by James I. The transepts and nave were never completed; when William died, his son put up a wall at the end of the choir and roofed what had been built to date. In 1650 Cromwell’s troops used it as a stable, although it survived remarkably well. In 1842, Queen Victoria visited what was then a romantic ruin and declared it a jewel worthy of preservation. In 2000, the partially preserved church was visited by around 26,000 people a year.

In 1446, William, the last Sinclair Prince of Orkney, began building a church to be called the Collegiate Chapel of St Matthew on the lands given to him in Scotland by James I. The transepts and nave were never completed; when William died, his son put up a wall at the end of the choir and roofed what had been built to date. In 1650 Cromwell’s troops used it as a stable, although it survived remarkably well. In 1842, Queen Victoria visited what was then a romantic ruin and declared it a jewel worthy of preservation. In 2000, the partially preserved church was visited by around 26,000 people a year.

Then, in 2003, Dan Brown published a book called The Da Vinci Code.

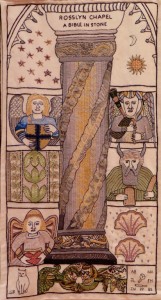

Rosslyn Chapel (as it is familiarly known) is where the book and movie come to their dramatic end. The building is an intriguing and mysterious embodiment of faith, filled with scriptural references in stone…and a whole raft of non-scriptural references. There are over 100 Green Men, alongside animals (both domestic and exotic), angels, and enough plant life to stock a forest several times over. There are strange mysteries and seeming anachronisms, too. Forty years before Columbus landed in the New World, some stone mason carved Indian corn into one of the window arches – suggesting that the legend about Henry, the first Prince of Orkney, wintering with the Micmac people in 1399 may, in fact, be true.

Now, my guess is that the vast majority of those wandering around Rosslyn with us two days ago (which felt somewhere close to the 26,000 they used to get in a year) don’t darken the door of a church on Sunday. So they were not on pilgrimage to some sacred site…any more than the folks at Knowth, or Castlerigg, or Maes Howe, or the Ring of Brodgar were seeking a place to be in touch with their own ancient heritage or personal traditions.

But there is something in the journey that brought those particular people to those specific places, something that is powerful, profound, and, perhaps, transformative. And for that, I think we owe a huge debt to Dan Brown, and to Kathleen McGowan – who has written a trilogy: The Book of Love, The Poet Prince, and The Expected One, and to Simon Toyne – who has also written a trilogy: Sanctus, The Key, and The Tower. We owe a huge debt to other writers and artists and gadflies and iconoclasts like them. They have done the general secular public a great service. They have reminded us that ‘faith’ is not an object, but a verb. And that using faith to browbeat (or murder) someone who disagrees with us is not only impolite, it is dangerous.

They have invited us to ask questions about what we have been told to believe, about what we think we are supposed to believe, and about what we think we do believe. They have reminded us that stories are over-written, preserved, slanted, and redacted by those in power. What we hold as Truth at any given moment in history needs to be taken with a good hefty cup or four of salt.

Brown and McGowan and Toyne have dared to read between the lines of what many people have come to believe is religious Truth (in these three cases, Christian Truth). They have suggested that we may want to remember that the doctrine that provides the lens through which we read scripture (a document that is already heavily redacted) is a human construct specific to its time and place and to the authorities who had the power to enforce what they wanted other people to believe.

Not by coincidence, this same process applies to economic and social and political documents, too. Which brings us to the Fourth (of July). You wondered if I was ever going to get here, didn’t you?

Here is the connection: We do not know what the writers of the Constitution meant with any certainty (any more than we know exactly what the writers of the biblical books meant.) We can take a guess, of course. But that’s all it is: a guess. And we can’t be sure what was motivating them. We can be absolutely certain that it wasn’t one, pristine, absolute Truth; it was a whole panoply of ideas and beliefs…there were forty men who crafted and/or signed the Constitution. Have you ever worked with a committee of forty? We also know that they were writing it back at the end of the 18th century. And we know that there were lots of things people believed as absolute truth at the end of the 18th century that we now know are completely wrong. But those beliefs influenced the world view of the men who wrote the U.S. Constitution.

It is a surprisingly forward-looking document for its time, but it is not holy writ. [In fact, one could argue that holy writ isn’t holy writ, but I don’t have time in this blog.]

It is a surprisingly forward-looking document for its time, but it is not holy writ. [In fact, one could argue that holy writ isn’t holy writ, but I don’t have time in this blog.]

I would like to propose that it might be nice if we (at least the citizens of the United States who are reading this) were to take the Constitution with a modicum of faith…not someone’s preferred (political, economic, social, or religious) doctrine, but faith (the verb). It might be productive to consider that the original document remains a work in progress; and therefore, asking questions and changing our answers, is part of the process of growing as a nation. Changing a comma (or a clause or our understanding of a concept) is not going to release the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. I would like to propose that in our search for the absolute Truth, we might want to retain a smidgen of humility and entertain the possibility that Truth just might change with the circumstances (just the way that water boils at a lower temperature in Denver than it does in Boston).

I would like to propose that one of the healthiest attitudes we can bring to the Constitution (and the other documents that undergird our nation…and to holy writ, for that matter) is a sense of wonder. Literally. And maybe we should wonder more and dictate less. On this Independence Day, I would like to propose that we stop living in the self-imposed prison of certainty and go frolic — at least for today — in the meadow of curiosity (and maybe celebrate with some fireworks).

–Andrea

Text © 2015, Andrea La Sonde Anastos

Photos © 2015 Immram Chara, LLC

NOTE: The first photo is the outside of Rosslyn Chapel (no photos are allowed in the chapel proper). The next three images are from The Great Tapestry of Scotland — 160 panels embroidered by over 1000 Scottish needleworkers, telling the story of Scotland from pre-history to the present. The final photo is from Bodnant gardens — living fireworks.